Imagine walking into a room and accidentally knocking over a cherished vase. When you say, ‘I broke the vase,’ the words carry a weight of personal responsibility, guilt, and accountability. The emotional temperature is immediate and intense. Now, if someone else reports, ‘The vase broke,’ the tone shifts. It becomes less confrontational, more detached, almost neutral. The event remains the same, but the way it is framed through language radically alters how we perceive responsibility.

This subtle yet profound difference illustrates a vital question: how does grammar influence our attribution of blame? Beyond mere syntax, language subtly guides our moral judgements, shaping perceptions of intent, culpability, and severity. As language learners, educators, or communicators, understanding this invisible power can help us navigate social interactions more consciously. In this blog post, we will explore how the structure of sentences, syntax, that is, does not merely organise words; it actively participates in the moral and social negotiation of responsibility. We will look at the linguistic mechanisms behind blame, cultural variations, psychological impacts, and the implications for teaching and technology in the age of artificial intelligence (AI).

The Invisible Power of Syntax

Agency in Grammar

At the core of blame lies the concept of agency — the doer of an action. In linguistics, we often talk about agents (the doers), patients (the receivers of actions), and actions themselves. For example, look at the following sentence:

The child broke the window.

The agent is the child; the action is broke; and the patient is the window. English typically emphasises the agent, especially in the subject–verb–object (SVO) order, which makes responsibility explicit.

However, what happens if we shift the structure?

The window was broken.

The agent becomes more ambiguous or hidden, potentially obscuring responsibility. This shift from active to passive voice changes the focus and the moral weight assigned to the event.

Why Blame Is Linguistically Malleable

Many assume grammar is neutral, a mere set of rules for constructing sentences. In reality, syntax is a powerful tool that influences how we interpret culpability, intention, and moral severity. The way a sentence is framed can either foreground responsibility or diminish it, often without conscious awareness. This malleability makes language a subtle instrument in social and moral negotiations.

How Sentence Structure Alters Perceived Responsibility

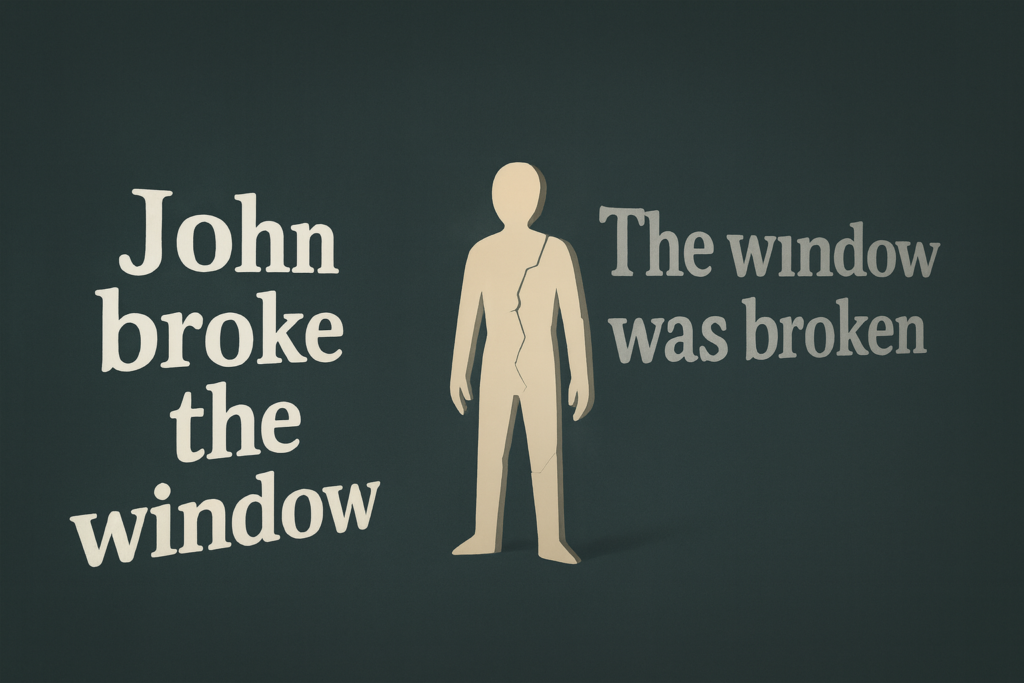

Active vs Passive Voice

The most familiar syntactic shift affecting blame is the contrast between active and passive voice.

—Active: John broke the window.

Here, the responsibility is explicit. John is clearly the agent, and the moral weight lies with him.

—Passive: The window was broken.

The responsibility is less clear. The sentence omits the agent, thereby softening blame or making the event seem more accidental.

In scientific or formal writing, passive constructions lend a tone of objectivity: for example, ‘The experiment was conducted.’ However, in political or media contexts, passive voice can serve as a rhetorical shield, deflecting blame or responsibility.

Middle Voice and Erasure of Agency

Languages such as Sanskrit or Greek, and even certain constructions in English, employ a middle voice or similar structures that focus on the subject’s involvement without specifying agency. For example,

The vase broke.

This sentence implies that an event happened to the vase, with no explicit agent. Now this allows speakers to describe accidents or mishaps without assigning blame, which is useful in cultures valuing harmony and face-saving.

Nominalisation as Blame Dilution

Nominalisation, which is transforming actions into nouns further abstracts responsibility. For example,

Mistakes were made.

This expression is a prime example of blame dilution. It removes the agent, making it sound like an impersonal fact rather than an accountable action. Such linguistic strategies are common in politics and corporate communication to avoid direct responsibility.

Hedging, Modality, and Softening

Using modal verbs and hedging language also influences blame. The the following for instance:

—’The report seems to have been misplaced.’

—’It might have been overlooked.’

These constructions reduce certainty, thereby diluting responsibility and making accountability more ambiguous.

Cross-Cultural Syntax and Blame

How Languages Encode Agency Differently

English tends to foreground the agent, emphasising responsibility. However, many other languages encode agency differently. Consider the following examples:

—Spanish: Take, for example, the sentence ‘ Se me cayó el vaso [The glass fell from me].’ This construction, called se passive, shifts blame from the agent to the event, framing it as an accident. It is a common way in Spanish to express unintentional mishaps, emphasising the event rather than the doer.

—Japanese: In Japanese, it is common to use autonomous or accidental constructions that emphasise the event rather than the agent, aligning with the cultural norms of humility and face-saving. A typical example is ‘ガラスが割れました [Garasu ga waremashita]’, translated as ‘The glass broke.’ In this sentence, the verb 割れました (waremashita) is in the passive or autonomous form, which emphasises the event (‘broke’) without explicitly stating who caused it. It can be translated as ‘The glass broke’ or ‘The glass has broken,’ with no agent specified. This structure allows the speaker to describe an accident politely and humbly, avoiding direct blame on any person.

—Indic Languages (e.g. Hindi, Bengali): In Hindi, Bengali, and similar languages, it is common to frame mishaps as events rather than assigning explicit blame, often using constructions that focus on what happened or the experience itself.

For example, take the Hindi sentence ‘मेरा मोबाइल गिर गया। [Mera mobile gir gaya],’ translated as ‘My mobile fell.’ Here, the focus is on the event (‘fell’) rather than who caused it. The phrase गिर गया (gir gaya) is a simple past tense verb meaning ‘fell’, with no subject or agent specified, although मेरा मोबाइल (‘Mera mobile‘, translation ‘my mobile’) indicates ownership. This structure communicates the mishap without directly blaming anyone or emphasising responsibility, which aligns with social values of harmony and face-saving.

Similarly, take this sentence in Bengali: ‘আমার মোবাইল পড়ে গেল।[Amar mobile pore gelo],’ also translated as ‘My mobile fell.’ Again, the emphasis is on the event (‘fell’) rather than on who caused it, fostering a tone of acceptance and harmony.

Cultural Attitudes Towards Accountability and Face-Saving

Linguistic structures are intertwined with cultural norms. In some societies, explicit blame may be considered rude or disruptive, leading to language that minimises responsibility. In English-speaking cultures, however, directness is often valued, even when it involves assigning blame.

In India, where social harmony and face-saving are important, indirect constructions and contextual cues often serve to diffuse responsibility, especially in hierarchical relationships. For instance, a manager might say, ‘The report was not as expected,’ instead of directly blaming an employee, allowing blame to be shared subtly.

The Psychology Behind Blame Framing

Cognitive Processing of Agency

Psychological studies indicate that people assign blame more readily to the grammatical subject of a sentence. Eye-tracking experiments show that when reading active sentences such as ‘The boy broke the lamp,’ readers quickly associate guilt with ‘the boy’. Conversely, in passive sentences, the responsibility is less immediate.

Emotional Impact

Explicitly mentioning the agent triggers stronger emotional responses, such as anger, judgement, or moral outrage. In contrast, agentless or passive constructions tend to reduce emotional arousal, making blame less intense and more socially palatable.

Media and Political Examples

Media headlines often manipulate syntax to influence public perception. For example,

The city’s infrastructure failed during the storm.

Vs

The city failed to prepare for the storm.

The passive version obscures responsibility, whereas the active version assigns blame directly. Politicians and organisations frequently employ passive voice to mitigate backlash during crises or scandals.

When Grammar Becomes a Tool, Intentionally or Not

Everyday Conversations

Language shapes emotional and moral responsibility in daily interactions:

—’You made me upset.’ (blame directed at the other)

—’I felt upset.’ (blame shifted inwards)

Such subtle shifts can influence conflict resolution and emotional health.

Education, Workplaces, and Conflict Management

Teachers might say, ‘The class was disrupted,’ avoiding direct blame, or managers might frame feedback as ‘Some improvements are needed,’ to soften criticism. These syntactic choices help maintain rapport and reduce defensiveness.

AI-Generated Text and Accountability

Large language models (LLMs) often default to passive constructions, raising questions about responsibility. When AI-generated content blames or exonerates entities, understanding the grammar behind blame becomes crucial in assessing accountability.

Teaching Implications for English Educators

For teachers of English, awareness of how grammar manipulates blame is essential.

—Critical Literacy: Help learners recognise blame-framing in media and political language.

—Linguistic Awareness: Encourage learners to analyse how their native languages handle agency and accidents, fostering cross-cultural understanding.

—Practical Exercises: Have learners rewrite sentences to shift responsibility; then discuss how meaning and emotional tone change with the rewriting.

By integrating these strategies, educators can equip learners not only with grammatical competence but also with moral and social awareness.

Conclusion: Language Shapes Accountability — So Use It Mindfully

Language does more than describe reality; it negotiates responsibility. Grammar is an ethical tool that can either clarify accountability or obscure it behind layers of syntactic subtlety. Whether in everyday conversation, media headlines, or diplomatic speech, the way we structure our sentences influences perceptions of blame and guilt.

As responsible communicators, writers, and thinkers, we should become more conscious of these linguistic nuances. Recognise how syntax can serve justice or injustice, accountability or denial. Use language with intention, knowing that grammar does not just reflect reality but shapes it.

So, the next time you craft a sentence, ask yourself: are you assigning blame clearly, softly, or not at all? Because, ultimately, grammar is not just about words; it is about responsibility.

Discover more from Methods and Musings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.